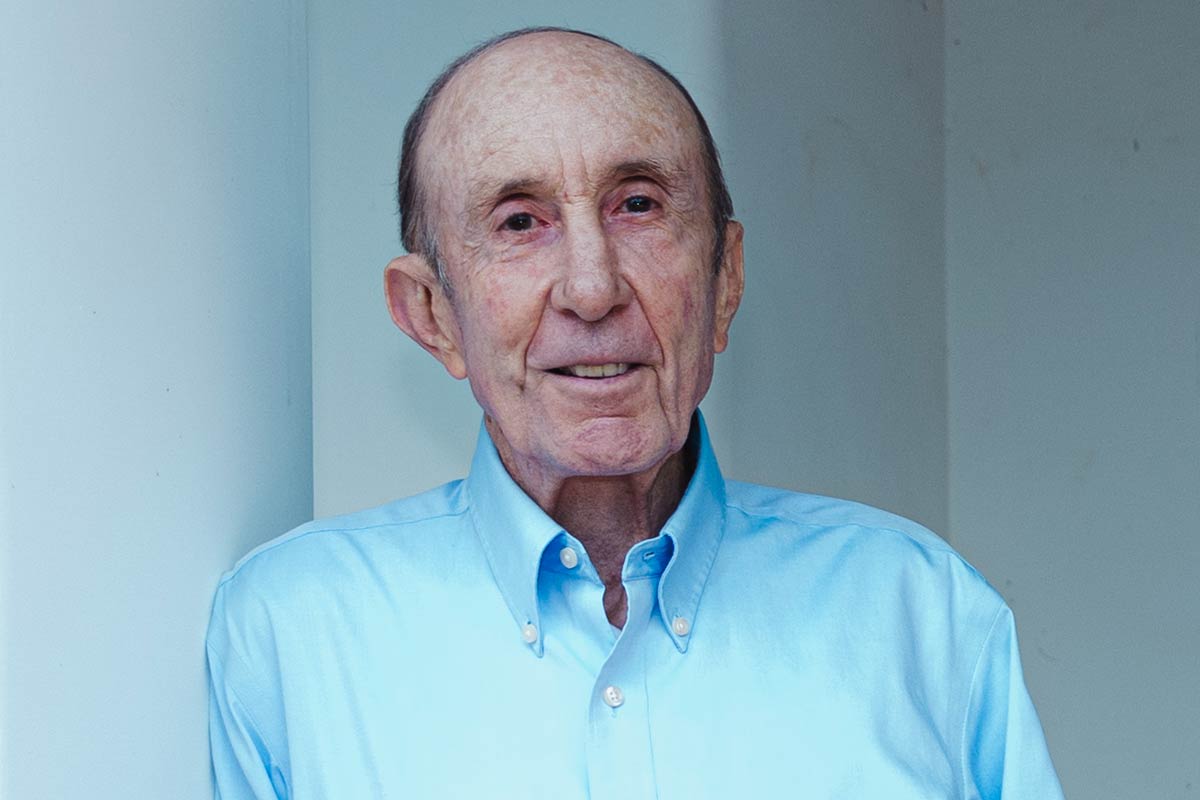

David Cannell is always willing to help.

He served as an in-depth consultant to NASA’s Physics of Hard Spheres Experiment (PHaSE) microgravity experiment, which flew on the Space Shuttle twice. He received the American Physical Society’s Outstanding Referee award, given to scientists who have been exceptionally helpful in assessing manuscripts for publication. He helped legions of undergraduates internalize the step-by-step reasoning of a physicist. He is a trusted resource for former student Jason Latimer, world champion magician and cohost of the Science Channel’s SciJinks. He once saved a baby squirrel by feeding it every hour, even while aboard a flight.

Now Cannell is helping young scientists— and the Hertz Foundation—by endowing the David and Louise Cannell Fellowship.

“I have been helped by so many people, over such a long period of time, I think it is only natural to try to help others,” he said.

One of five children, Cannell grew up in rural Maryland. He entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from a parochial high school that was devoid of calculus—or even pre-calculus— yet he managed to graduate near the top of his class. “That process was formative, to say the least,” he said.

While finishing his PhD in experimental condensed matter physics at MIT, he was offered a faculty position at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). That is when he felt the full impact of his Hertz Fellowship.

“The Hertz Fellowship really added to my confidence in my own work and in judging other people’s work,” he said. “I was told that I would be throwing my career away by going to UCSB, but I thought the professors there were just as good as any other faculty, and the work they were doing was just as important. My judgment was right. UCSB is now recognized as having one of the very best physics departments in the country.”

Today, the faculty includes three recipients of the Nobel Prize in physics and six Hertz Fellows—Lars Bildsten, John Gilbert, Beth Pruitt, Omar Saleh, and Scott Shell, in addition to Cannell, who is professor emeritus.

Cannell joined the UCSB faculty in 1970 and enjoyed teaching there until his retirement in 2012. The first class he taught—one he went on to teach to more than 1,200 students—was physics for biology and pre-medical majors. “To me, physics was physics. It meant learning the laws of physics, how to analyze physical situations using whatever mathematics was relevant, and creating an ironclad chain of logic,” he said.

“I taught students the process of step-by-step reasoning, a new way of thinking for most of them. The neatest thing was to realize they were thinking, ‘Wow, I’m smarter than I thought I was.’ That was a great feeling.”

The course that brought him the most pride, though, was a one-year physics lab he created for students in UCSB’s College of Creative Studies, a program for particularly talented students, including 1979 Hertz Fellow Alex Filippenko, winner of the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics.

“I realized that for a physics major, an engineer, or a biology student, to work in a research lab is an extremely important, even formative, experience. But at the same time, who’s going to take an undergraduate into their lab?” he said.

So Cannell developed a class to prepare students for the experience. The point of the course was not to teach students, but to let them learn for themselves. Through a series of experiments, students were asked to investigate and write papers on different systems—the properties of a pendulum, flow through capillary tubes, learning to program, and working as a team to design and build instruments, for example.

“I wanted to teach them the essence of research, which is to look at something and ask yourself some interesting and important questions, and then figure out some way to answer those questions unequivocally and clearly,” Cannell said. “I let them work together and teach themselves. The students found it very tough, but time and again I was told, ‘I learned so much in that course.’”

Over the decades at UCSB, Cannell also was recognized for his research. He was awarded an Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship in 1973, a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in 1978, and in 1987, he was elected a fellow of the American Physical Society. His research was supported by the National Science Foundation and NASA. He served as a consultant and member of the ground control team for NASA’s PHaSE experiment, which flew aboard two shuttle missions to study the formation of hard-sphere colloidal crystals in microgravity. He was also co-principal investigator with Professor Marzio Giglio of the University of Milan on GRADFLEX, an experiment flown by the European Space Agency as part of the Foton M3 mission.

Today, he is happy to be leaving a legacy in the form of an endowed fellowship that bears his name as well as the name of his late wife, Louise, who died in 2023. Cannell met Louise in 1966 on the flight where he was carrying a shoebox with a tiny squirrel that had been blown from its nest during a storm and was feeding it with an eyedropper. The squirrel survived and lived with Cannell for a year or two. Cannell married Louise in 1967, the same year he received the Hertz Fellowship. They were together for more than 55 years and have a daughter, Catherine Cannell.

The Hertz Fellowship made their lives easier when Cannell was in graduate school. He embraces the idea of paying it forward in perpetuity. “I’m just trying to help other people. I feel I have an obligation to do that, and it’s a cheerful obligation. I feel very good about doing this.”