Tackling Climate Change Through Airplane Contrails

Hertz Fellow Thomas Dean has applied his creativity, dedication, and engineering mindset to everything from building a military career and solving cybersecurity problems to leading climate change research and Hertz mentorship efforts.

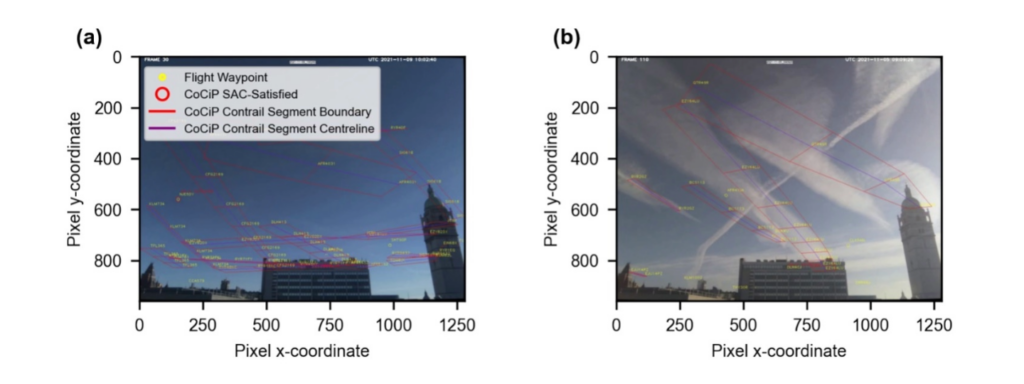

Peer into the sky on a cloud-free day, and against the clear blue, you may see wispy white contrails left behind by airplanes as they jet around the world. These cloud-like trails form when the hot exhaust from planes meets the cold moist air in the atmosphere, and they are responsible for as much as half of the global-warming effects of aviation.

Hertz Fellow Thomas Dean, a research scientist at Breakthrough Energy, is using his engineering background to better model the consequences of contrails, as well as ways pilots could avoid creating them in order to minimize climate change.

“You can essentially reroute planes not to fly through the small parts of the atmosphere where the highly warming contrails are formed,” says Dean. “The costs of doing this are tiny, but we think it can really mitigate anthropogenic climate change.”

Dean credits the Hertz Foundation with opening up new doors for him throughout his career—he first started working on contrails, for instance, thanks to a connection with Hertz Fellow Ian McKay. Because of the value of these sorts of connections, he has remained highly involved in the Hertz community, mentoring early-career researchers, helping organize summer conferences, and launching the Hertz LBGT+ interest group.

Jumping Into New Fields

Dean has not always focused on contrails—or climate change. His undergraduate and graduate degrees are in electrical engineering, and he says that he is always on the lookout for new, interesting research questions that let him combine engineering, applied mathematics, and real-world problem-solving.

“It’s a fun challenge for me to jump into a new field and learn,” says Dean. “I’ve always just enjoyed research and learning and being a lifelong student.”

As an undergraduate at the United States Military Academy at West Point, Dean carried out research on differential equations. When he began graduate school at Stanford, he then had the chance to work with Andrea Goldsmith, who runs a lab focused on wireless technologies. Although his own projects looked at the underlying information theory and signal processing algorithms behind wireless networks, Dean liked how applied the research was—ultimately enabling him to improve and better secure new technologies.”

“I studied engineering, rather than physics or mathematics, so that I could solve real-world problems,” he points out.

Between completing his master’s and Ph.D. work at Stanford, Dean served in the U.S. Army as a signals intelligence officer and then a cyberwarfare officer, giving him additional experience in network and software security.

Back at Stanford, he appreciated the flexibility that the Hertz fellowship gave him to pursue multiple different projects—including some that he wasn’t sure at the outset would work.

From Cybersecurity to Climate Change

After finishing graduate school, Dean continued in the same vein of work he’d started in the Army—but this time as a government contractor with Booz Allen Hamilton. He spent two more years working on issues related to network security and cryptography. But Dean was ready for a new problem to tackle, and started looking for opportunities outside of the defense industry. Then, Ian McKay — whom Dean had met at Hertz events — offered him the opportunity to work on modeling airplane contrails.

“It started out as a part-time job, but I just found it really cool,” says Dean. “It’s mostly a weather forecasting problem, but there are also a lot of challenges with imaging contrails in order to validate models and contrail estimates.”

Photo Credit: Jade Low, Imperial College. Image from “The Arctic’s Future: Understanding Ice Dynamics and Climate Change,” published in EGUsphere, 2024. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Breakthrough Energy, where Hertz Fellows Cooper Rinzler and Rajeev Ram also work, aims to support technologies that move the world toward net-zero carbon emissions. Dean’s job on the Contrails team gives him the chance to delve into all areas of contrail science and engineering. Much of his research initially focused on the large scientific challenge of how to quantify and predict contrails—as well as how changing flight patterns could minimize contrails. But there are also numerous questions about how these flight changes would play out. For instance, how would slight route changes impact pilots’ cognitive workload? What sort of information would flight dispatchers and flight planners need about contrail avoidance?

Dean says the field has enough questions like this to keep him engaged and busy, and his skill at combining information theory with statistical tools is useful in looking at large, complex weather and contrail data sets. But in the future, his big-data approach could also be applied to other questions unrelated to contrails; Dean is keeping an open mind about where his career takes him.

Giving Back to Hertz

Recently, Dean has begun to make annual gifts to the Hertz Foundation as a way to give back to the foundation that has helped shape his career. He has also offered his time on workshop and retreat committees—including helping to organize the inaugural Hertz Topical Forum: Energy—as well as volunteering as a reviewer for the Hertz Thesis Prize.

In addition, Dean proposed the creation of the Hertz Foundation LGBT+ interest group, which he now leads. Dean, who is gay, is passionate about making sure people with diverse identities feel welcome within the Hertz community.

“I served part of my time in the military under ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’ so being visible is not something I’ve always had access to,” says Dean. “I wanted Hertz fellows to be able to have visibility.”

Dean is confident that Hertz will continue to supply him with opportunities, resources, and ways to further his career. He says he is continuously impressed by how willing very senior, late-stage career scientists are to participate in Hertz events and have casual conversations about science. In turn, he hopes to model this mentorship and openness to remaining active in the Hertz community.